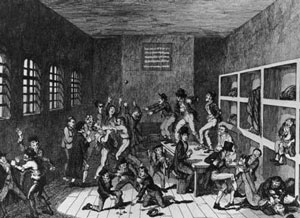

Imagine spending two weeks or more in a jail cell like this because you owe money to someone. Well in some American states, this is reality. Photo Credit: texasobserver.org

The concept of debtor’s prisons today, most would consider a past uncaring practice by the criminal justice system. A practice viewed as a callous and unacceptable way to punish those incapable of paying off money owed to another. To place people in jail for being unable to pay their bills is a notion that appears heartless as well as hypocritical. The imprisoned cannot pay the bills, thus, debtor’s prison makes being poor a crime. This is why once again the Supreme Court ruled that it was an illegal practice in protection of all U.S. citizens in 1983.

In the American Civil Liberties Union’s (ACLU) 2010 report, “In for a Penny: the Rise of America’s New Debtor’s Prisons,” the 1983 Bearden v. Georgia Supreme Court case concludes that the imprisonment of someone who has made every attempt to pay a debt, but still cannot pay the bill, violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. Danny Beardon, convicted of theft and burglary in 1980, was sentenced to three years of jail and $750 in fines. Beardon borrowed money to pay the immediate payment of $200, but when he lost his job, the court forced him to serve his remaining probation in jail because the rest of the fine was not paid. The Fourteenth Amendment clause that the Supreme Court made its ruling on identifies that no state has the ability to deny any person their equal protection rights if covered under the jurisdiction of the law. By placing Bearden in debtor’s prison, the Supreme Court determined that the state denied him equal protection as an American.

The Supreme Court case in 1983 appears to be clear; “Americans cannot be imprisoned because of money they owe to another.” However, ways around the ruling have been found and debtors’ imprisonment is becoming a more and more widespread practice. Those owing money are not jailed for the debt they owe, “but rather for failing to respond to court hearings, pay legal fines, or otherwise showing ‘contempt of court’ in connection with a creditor lawsuit” according to Alain Sherter’s CBS Money Watch article, “Jailed for $280: The return of debtor’s prisons.”

Originally outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1833, the resurgence of American debtors prisons is destroying lives. Photo Credit: cucollector.com

The prevalence of debtors’ prisons today is linked to the current economic downturn. The Huffington Post’s article by Jillian Berman, “Debtors’ Prison Legal in More than One-Third of U.S. States,” explains that since 2010, judges have issued at least 5,000 warrants related to people owing money. However, Berman says that an absence of national statistics on jailing those who owe money does not show the reality of how many are actually in jail because of debts. Joblessness, the decline of home values, and almost stagnant wage growth all contributed to a person’s inability to pay their bills. Berman adds that this has led to the more rigorous practice of incarcerating those debtors.

Debtors’ prisons were originally abolished in 1833 by the Supreme Court as intolerable treatment of the poor. At that time, the prisons did not pay for food, fuel, or furniture to those incarcerated for not having money to pay their debts. Extended families and charitable societies were the only means for incarcerated debtors to survive while in jail. The Digital Histories’ article, “Social Reform and the Problem of Crime in a Free Society,” states that; “Increasingly, reformers regarded imprisonment for debts as irrational, since imprisoned debtors were unable to work and pay off their debts.” Piece by piece reformists’ ideas eventually led to the abolishment of debtor’s prisons and the U.S. social transformation requiring better treatment for all Americans.

As cash-strapped states contend with balancing budgets and businesses experience less than projected profits, debtor’s prisons returned. Although today’s prisoners are fed, clothed, and housed by the local county or state facility, and the system is not quite as barbaric as it previously was, the concept of imprisoning anyone for a debt is unconstitutional to say the least. With some debtors owing as little as $200, the states and other entities due money, spend more to jail them than the initial amount owed. The ACLU indicates, “In fact, incarcerating indigent defendants unable to pay their LFOs [legal financial obligations] often ends up costing much more than states and counties can ever hope to recoup.” The ACLU report calculates that a Washington man’s $60 debt led to two weeks in jail, which cost taxpayers around $1,700.

Similar to debtor’s prisons of the past, today’s sentences are for miniscule amounts of money owed. The Associated Press (AP) finds that a $280 medical bill caused breast cancer survivor, Lisa Lindsay’s arrest, only to find out later that the bill was an error on the part of the hospital and collection agency. Missed payments as low as $25, has led to intimidation by sheriff’s deputies, courts, and county jails in portions of Illinois, which are all funded by taxpayer dollars, according to AP.

The highest numbers of those arrested are black and Hispanic, once again, racism and poverty lead the charge. Photo Credit: consumerist.com

Also akin to past debtor prisons, the jailing of debtors disrupts lives, and creates a cost increase in social welfare programs for families when the debtor loses their ability to provide financial support due to being chained to the criminal justice system, as well as another threat of jail if the debt is not paid. The ACLU report says that after jail, debtors deal with problems adjusting emotionally and financially due to reduced incomes, worsened credit ratings, grim employment, and housing prospects.

Debtors’ prisons appear to be a war against poverty because they place the financial burden of the state and county woes on the backs of those living paycheck to paycheck. The ACLU also uncovered that this dark-ages practice of criminal justice also appears racially distorted with Hispanics found to have higher LFOs than white debtors in Washington. And the over-representation of blacks and Hispanics in prisons nationally are a skewed symbol of how minorities are tried in the criminal justice system.

Cash-strapped states looking for ways to balance their budgets are unfortunately, targeting the poor to get the books in the black. The renaissance of these prisons is resurrecting a practice that is classist, racist, and immoral. When those with power are in the red, does that mean that social reform and our rights encapsulated in the Fourteenth Amendment can go on the back burner?

Sources:

Berman, Jillian. Debtors’ Prison Legal in More Than One-Third of U.S. States. (November 11, 2011) Retrieved from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/11/22/debtors-prison-legal-in-more-than-one-third-of-us-states_n_1107524.html

In for a Penny: The Rise of America’s New Debtors’ Prisons. American Civil Liberties Union. (2010) Retrieved from: http://www.aclu.org/files/assets/InForAPenny_web.pdf#page=82

Ill. lawmakers target practice of jailing debtors. Associated Press. (April 19, 2012).Retrieved from: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505247_162-57416794/ill-lawmakers-target-practice-of-jailing-debtors/

Sherter, Alain. Jailed for $280: The return of debtors’ prisons. CBS Money Watch. (April 20, 2012) Retrieved from: http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-505144_162-57417654/jailed-for-$280-the-return-of-debtors-prisons/

Social Reform and the Problem of Crime in a Free Society. Digital History. (May 6, 2012) Retrieved from: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=626

Written by Jodie Blankenship

Article reprinted with permission of USAonRace.com

No Responses to “America Exposed: The Return Of Debtor’s Prisons Ruining Lives & Families”